The Graphic Design of Ham Radio: QSL Postcards

When amateur radio operators connect, confirmations come as a QSO over the radio. A second confirmation — featuring a distinct graphic language of its own — often follows in the form of a postcard.

Two quick notes:

Thank you all so much for reading and subscribing. This is my first story in the new Selectism newsletter format, and I hope you find as much love in the graphic design of these postcards as I do. If you liked the story, I’d love to hear from you. And if you didn’t—honestly, I want to hear that too.

All postcards featured throughout are original pieces from my archive, scanned specifically for this story.

I’ve been fascinated by radio since I was a kid. My grandfather had two radios: one was a boombox-style AM/FM cassette player; the other the other—more prized—was a Sony shortwave World Radio, strictly off-limits to the grandchildren.

Both sets of grandparents were immigrants, and world band radio was their lifeline to what was happening back in Portugal.

Three aspects of radio pulled me toward my future work in culture and deepened my love for the format: sports, news, and music. But getting there required a few things: a cassette recorder, a world band radio, a record store, and a library.

Sports

My uncle Adolfo was infamous for holding a shortwave radio to his right ear—just about all day Sunday—to listen to live football broadcasts from Portugal. He held it like we hold smartphones today, but more in the way people hold a phone to their ear while it’s on speaker. On the other end, game announcers would scream “goooool!” while a photon beam–like screech blasted from the radio speaker, to the joy of no one in Adolfo’s vicinity. (The New York Times once described this as “the siren song of soccer” during the 2014 World Cup—and again in a mashup of all 169 goals from the 2018 tournament.)

News

My fascination with radio didn’t end there. As a kid, I would read articles from my local paper, the Journal Inquirer, into my father’s Marantz Superscope CDC-302a cassette deck, practicing daily to get the tonal inflections just right. I tried my best to sound as composed and put-together as Peter Jennings or Dan Rather—never mind the fact that both worked their craft on television, not radio.

I loved talking into the mic. I loved trying to sound as articulate as possible. And, quite frankly, I probably just enjoyed hearing myself talk. Either way, I was reading the paper at an early age.

Music

Up late one night around the age of nine, I tuned into WRTC FM Trinity College Radio, a small university-run radio station just up the hill from my grandfather’s house in Arnold Street in Hartford. Trinity College Radio was the shit—I just didn’t really know it at the time.

WRTC D.J.s introduced me Newcleus, Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force, Kraftwerk, and UTFO with their battle track, “Roxanne, Roxanne,”—arguably the first song to receive a “response” diss track, later known as the Roxanne Wars.

Without realizing it I was being exposed to culture, society, and politics through sounds, beats, and the D.J. Music—the third part of the radio trifecta—would become my most consistent go-to for any type of feeling or emotion.

I feel lucky to have discovered WRTC at such a young age.

At nine, I wanted a real copy of “Jam on It,” to replace my cassette copy recorded hot off the radio. My father told me that if I found a shop that carried it, he would drive me to buy it. I called around and discovered a bunch of new shops with closet being Record Breaker in Manchester, CT. Record Breaker, along with the library, would play an important role in helping me see beyond the suburbs of New England. ¹

My father kept telling me to buy the vinyl, rather than the cassette I preferred. For one, I did not have a record player of my own; I relied on cassette decks to play my tunes. Looking back, my father was right.

While Record Breaker opened my ears to music, a big part of me was still fascinated with radio—not just the broadcast, but the business behind it. And my public library had the information I needed.

My library had it all: books, magazines, periodicals, newspapers, journals, microfiche archives, audio books on cassette and vinyl; and music on cassette and vinyl. The library was the shit—really.

My library helped turned me onto another aspect of the radio field I had avoided for some time: amateur radio, better know as “ham.”

Ham Radio

Unlike FM and AM radio, which broadcast music and news one-way for commercial, military, and private use, ham radio is designed for two-way communication between licensed operators. Each operator functions as a station and is identified by a unique call sign. Call signs matter—they tell you who is on the other end and where they were.²

To get a call sign, you just need to pass an FCC exam, usually offered by a local ARRL chapter. You didn’t even need a radio, honestly—just a strong understanding of math, physics, electronics (think Ohm’s Law), operating procedures, and radio wave propagation.

And at ten? I had no fucking idea how I was going to learn any of it. I had better things to do—like build forts, play soccer, and break stuff.

Fast forward to COVID, and things changed. Like everyone else, I was home, doing whatever I could to stay busy. One afternoon, I was on YouTube learning how to fix old iPods (something I’ll still do for anyone, gratis), and the algorithm served me up some ham radio content. Radio hardware had come a long way—now you could get a solid, handheld, multiband two-way radio with a long antenna for under $40. It was finally within reach, 35 years later.

Four months later, I took the AARL radio exam and passed the entry Technician License. I was issued my call sign: KQ4NRH

Within hours, I was on local “radio repeaters”—open stations that extend signals across long distances—ready to try out ham radio shorthand. I called out:

“CQ, CQ, CQ, this is KQ4NRH calling CQ and listening,” ham code for: Is anyone out there?

If timing and luck had it, I would hear back “QSL.”

If CQ is at the start of a two way radio communications, and QSL as “I confirm that I received your signal report and other information,” then QSO is the extra filling in the middle.

QSO is the successful exchange of information between two stations. On my first QSL, that successful QSO included signal strength, weather, and location—known as QTH.

That was more than enough for me. I was so excited during the call that I lost track of the other operator’s QSO info—even his call sign. In today’s world, it’s nearly impossible to find that station again unless you reconnect. A logbook entry was fine, but there was another solution, one rooted in nostalgia: the postcard.

QSL Postcards

A QSL postcard is the physical proof of a connection made by two parties over the radio waves. The information shared on them helped operators like me understand what was happening on the other side of the call. They also confirmed that your logbook entries were accurate.

Postcards were also incredibly inexpensive, costing one cent to mail before 1952, when the price rose to two cents.

I began buying “collections” of postcards about a year ago. They’re not hard to find—eBay has so many QSL card lots that it’s easy to get lost trying to figure out where to start collecting. To bring some sanity to my already obsessive nature around ephemera, I stick to buying only pre-1950s QSL card lots (though I have plenty of examples from the ’60s and ’70s). To me, the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s were the golden age of QSL postcard graphic design.

Like most postcards, QSL cards carried a brief message and greeting on one side and a visual element on the other—often photographs or illustrations, both of which were common on QSL cards.

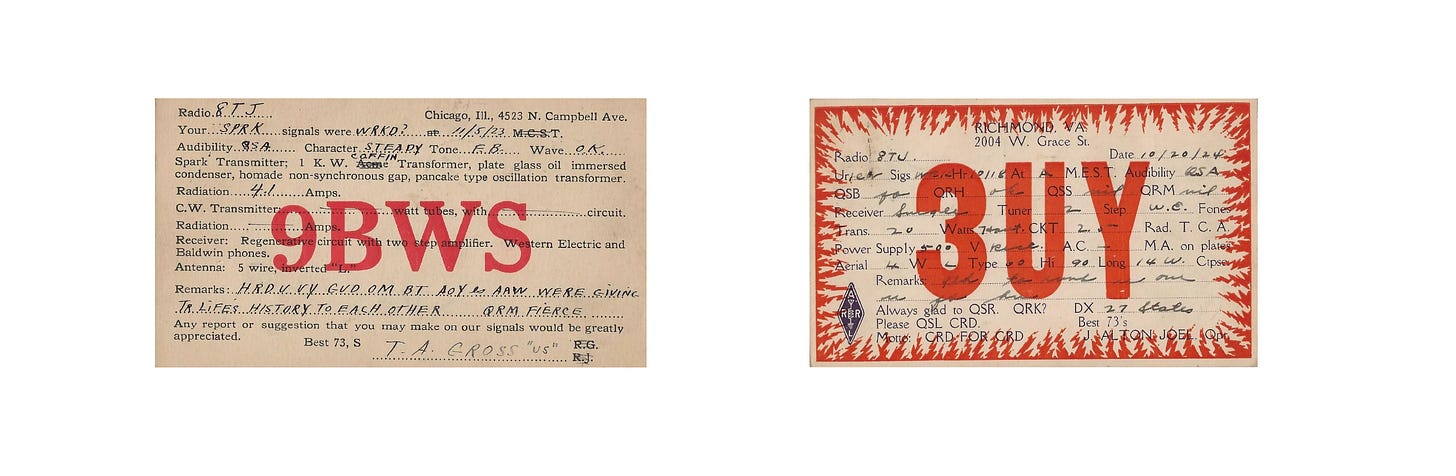

Pre-1940 QSL cards typically featured graphic elements that allowed for customization of call signs and locations. Printers across the U.S. offered bulk deals on QSL printing—$5 for 500 cards, or about a penny each.

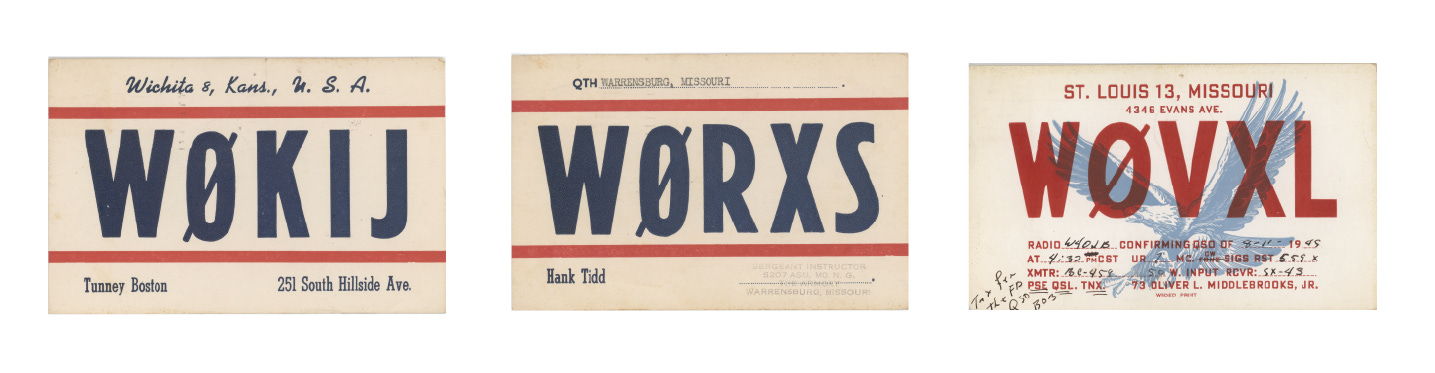

QSLs were your calling card in the ham radio world, so many operators took great care in choosing blocky, poster-style typefaces—punchy, bold, and easy to read from a distance.

United States

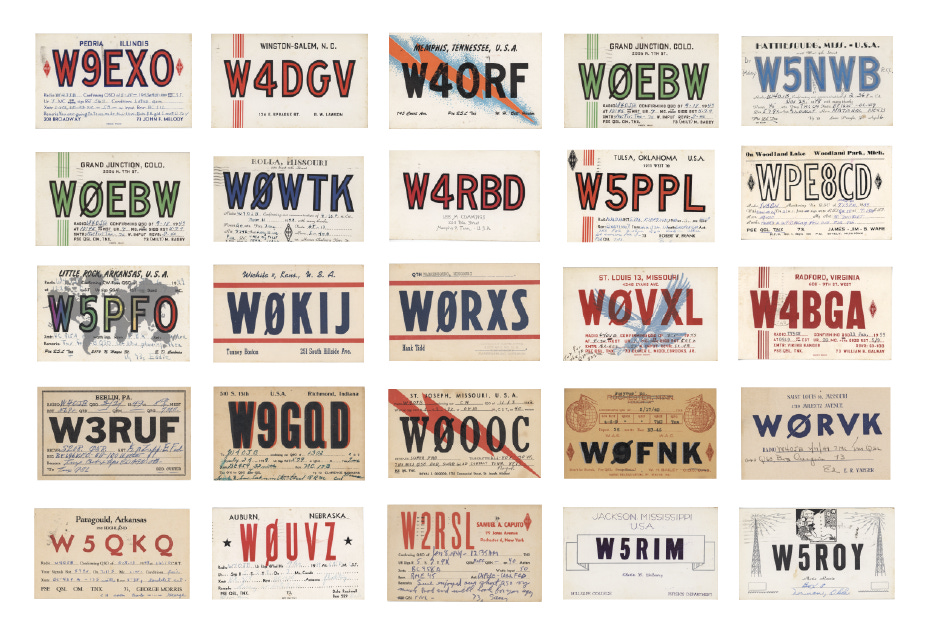

Take, for example, this collection of 25 QSL cards sent to B. Harnell (W4OJB) in Memphis, Tennessee, during the 1940s:

In the image, you’ll see the extensive use of block and poster print style typefaces common to QSL cards of the time. The top two rows feature my favorite of the block typefaces used during the 1940s.⁴ Decades later, I believe they stand the test of time for graphic design—as visually appealing today as they were 75 years ago.

Row three includes my favorite American call sign: W0RXS, out of Warrensburg, Missouri. W0RXS feels like early leetspeak to me, as do W0XWL and others—predating the term’s digital use by nearly 40 years.

Demeritorious Radio

Some radio operators mess up—they curse or say explicit shit on air, which is a no-no, or they botch their radio setups, causing unnecessary noise and things like “rippled modulation,” as seen above. When these slip-ups are picked up by official ARRL observers monitoring the same frequencies, you’ll likely receive a citation—technically not a real one, but more a gentle nudge.⁵

The ARRL Official Observer’s Cooperative Report contains some of the most distinctive language I’ve seen—meant to call out errors without issuing a formal citation. The tone is somehow both gentle and sharp at the same time.

This report is not a citation or a "bawling out" in any sense. It is simply a friendly notice from one amateur to another, calling attention to a condition observed that appears to violate an FCC regulation. The ARRL-Observer program is designed to help amateurs help each other, keep our bands clean, and assist all amateurs to avoid FCO citation, with potential risks to amateur operating privileges. In this your cooperation is requested.

Details above may suggest a special check by yourself, or with a nearby amateur to try to duplicate conditions reported, in order to initiate corrective measures. Chapter 23 of The Radio Amateur's Handbook, as well as several @ST articles may be of aid to you. Let's fix the signal today, OM. 73.

OM—short for “old man”—was common vernacular among radio operators, regardless of age.⁶ “73” meant “best regards.” Design-wise, this postcard was about as standard as a typewriter font—though one could hope never to receive one.

International QSL Cards

One fascinating note: when I began collecting vintage QSL cards, I noticed a lack of postcards from overseas hams. Turns out that during the 1940s, amateur radio operators were not permitted to communicate with international operators—largely due to wartime restrictions.

But recently, I came across an excellent collection from a ham operator in Venezuela: Dr. Rojas of Caracas, call sign WV5GN. Throughout the 1950s, Dr. Rojas went all out—collecting QSL postcards from nearly every corner of the globe, covering just about every continent.

Dr. Rojas was an avid ham operator, making contact with more than 75 stations—the total count of his collection. We see Spain, Portugal, France, Germany, Scotland, Czechoslovakia, Angola, and many more.

My three favorite cards from Dr. Rojas’s collection were sent from Italy, Panama, and Iraq. They share a bold use of uniform, standout call signs—and like many in my collection, they stick to that dominant red that runs through so much of QSL card design.

But this is just a glimpse of the millions of QSL cards still out in the wild. Their appreciation and collectability have risen and fallen over the years, with the occasional writer—like me—stumbling upon them and highlighting the graphic beauty they hold.

In 2020, author Roger Bova published QSL? (Do You Confirm Receipt of My Transmission?), a book showcasing 150 cards from a collection he discovered in a New York state antique shop. All were confirmed to the call sign W2RP. Roger’s book a great visual representation of QSL card design.

Footnotes

Years later, Record Breaker would open my eyes to zine culture where I discovered Maximimrocknroll amongst others alternative press titles.

Every country in the world, as well as stations in the Arctic and at sea, has a unique letter identifier for radio communication. For example, call signs in the United States begin with K, N, W, and A; in Spain, they start with EA, EB, and EC; in France, with F; and in Japan, with JA, JE, JF, JG, and JH, among others.

I met a guy at Record Breaker who had friends who recorded the very best DJ and producers on New York radio and mailed them up to Manchester. He was kind enough to make some dubs for me.

While the postcards were sent in the 1940s, it is very likely this block face has been in use going back to the 1930s.

With amateur radio license information being public record, it did not take much to figure out where said call sign was physically located.

YL (young lady) and XYL (ex–young lady, or wife) were both commonly used terms for female radio operators of any age.

Appendix

A Poorman’s Refresher on the History of Radio

Like most of these things, it started with a theory, some experiments, and eventually, confirmation.

In 1864, a Scottish physicist named James Clerk Maxwell predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves—including radio waves—using some math that’s way too complicated for me to understand.

Twenty-four years later, a German physicist proved Maxwell’s theory by generating radio waves in a lab. Then in Italy, a guy named Guglielmo Marconi sent the first tones, blips, and bleeps to a town just 1.5 miles down the road.

Two years later, Marconi landed in England to start the first telegraph company. Four years after that, telegrams were crossing the Atlantic—in Morse code—connecting Cornwall, England, with Newfoundland, Canada.

Tesla was in there too, doing wild stuff with spheres, electricity, and circuits—all of it tied to radio and electromagnetism.

But blips, beeps and tones of Morse Code were boring, and we needed audio!

Meanwhile, over in Thomas Edison’s New Jersey office, there was a Canadian named Reginald Fessenden dreaming about sending voice over radio waves. In 1890, after 14 years on the job, Fessenden left Edison’s lab to chase that dream.

He put in a solid decade of work, and in 1900, he transmitted the first human voice over radio waves.

That brings us to Christmas Eve, 1906, when—for the first time—music was broadcast. As expected, it was religious and classical: “O Holy Night” was sung and performed on violin, and a passage from the Bible (Luke 2:14) was read aloud.

At the time, most of the listeners were ships at sea—many had adopted the technology quickly after a string of intercontinental shipwrecks.

But radio was here across the United States, the first stations began coming online:

• 1920: KDKA (Pittsburgh) and WWJ (Detroit)

• 1921: WBZ (Boston) and KYW (Chicago)

Where the telegraph was great for sending short notes, hearing voice and music instantly over the airwaves was a whole other experience.

Things sped up quickly. Radio was now being used by commercial broadcasters for music and news, and by the military to connect ships at sea and beyond. But alongside those uses were the amateur radio operators—people like Irving Vermilya, who had been tinkering with radios since age 12.

In 1912, the same year the Radio Act brought regulation to the airwaves, Vermilya was issued what’s arguably the first amateur call sign in the U.S.: 1ZE.

By 1917, more than 6,000 licenses had been issued to hams across the country. By the end of the 1940s, that number hit 60,000.

The earliest known QSL card was sent by 8VX (W.E. “Bill” Corsham) of Buffalo, New York, in 1916.

Epic. The postcard designs and the citation are so good.

This was a great story for Selectism to spin the block on in 2025; welcome back.