Everything’s a clash in Jamaica

"Bikes, sound systems, lyrics—it’s always a competition." A conversation with Walshy Fire on the sound and emotion of dancehall culture.

My happy place? It’s a stack of unsorted, untouched records—just waiting to be discovered. Most of the time, that stack is decrepit and dusty, needing nothing more than a quick spritz with my favorite DIY record cleaning spray, and a wipe.

Other times—like this past weekend—I find records in a warped, soggy mess of cardboard that’s fused together. Think of a pulp-paper cube—LPs and sleeves molded together into a paper mache-like block. If you know Miami, you know flooding is common. Finding records in this condition isn’t rare. But working through them is a job best done outdoors: as you peel apart the soggy sleeves and extract each record, decades of dust and mold rise into the air.

The deeper I got into that mess, the more it became apparent I hit dancehall gold.

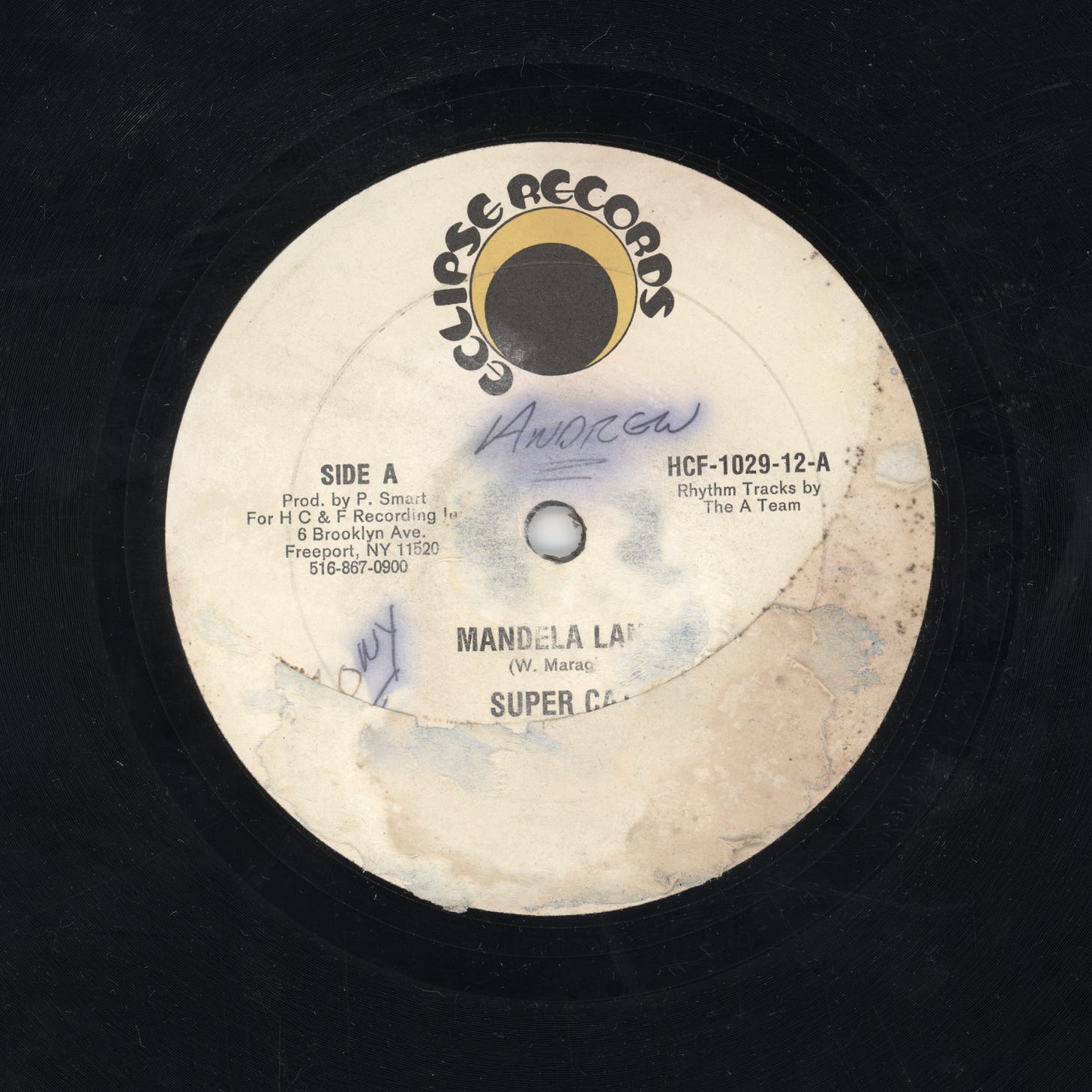

This super-rare 1994 Super Cat / Lilly Melody split 12-inch—“Mandela Land / Gimme Back” is one of the first records I pulled. It’s a tribute by the one known as Super Cat to Nelson Mandela. Like everything dancehall it ties back to politics and more.

Finding that stack of records feels like a manifestation, because the timing is wild: The same week I found the records, I sat down with Walshy Fire for an interview on his new book, “The Art of Dancehall,” which I featured in last week’s Five Things 01.

Coincidence? Maybe. But more likely, it’s one of those cases where the energy you put out brings something back to you.

“The Art of Dancehall” opens more doors—and YouTube tabs—than I expected. I found myself referencing old flyers from the book, then heading online to dig up legendary clashes from well known pioneers like Killamanjaro, David Rodigan, and countless other heroes of the music unbeknownst to me before the book.

Sound clashes happen on sound systems, and they can be brutal—even humiliating—for the loser. At the heart of it all are versions on dubplates: well-known tracks re-recorded with new, custom lyrics, often as direct lyrical weapons aimed at rival crews. That’s what hooked me.

How in the world do dancehall DJs convince artists—even global stars like Rihanna—to get in on the clash?

Back in 2014, Rihanna recorded a version of her hit “We Found Love” for Rebel Sound1—a dub that didn’t just diss heavyweights like Stone Love and BBK, but even took shots at her future husband’s crew, A$AP Mob. It’s YouTube gold.

This is raw power of audio warfare.

But I needed more. I needed to hear it straight from a master of the craft.

What follows is my conversation with Walshy Fire on all things dancehall, from clashing to culture, and everything in between.

Interview with Walshy Fire

Location: Novela Cafe Social, Miami.

Jeff Carvalho: So what was this—six, maybe seven years ago you had an idea for the book?

Walshy Fire: When I first had the idea? Yeah, about six years ago. I was just cleaning out my garage and came across all these boxes of flyers.

Jeff: How many do you think you found?

Walshy Fire: Oh man, boxes. And they’re important—not just to me, but because each one carries a story. Every flyer connects to a memory. I’d find myself staring at one for too long, just reliving it all. That’s when I thought, maybe other people would be into this too. That’s how it started.

When I met Shepard Fairey—he was like dancing with excitement. He told me, “You’ve gotta do a book!” H actually connected me with his publisher.

Jeff: How do you pitch a flyer book to a publisher?

Walshy Fire: You give them the idea and maybe a sample. But it wasn’t a hard sell. They got it immediately. It was just a super unique concept.

Jeff: Let’s shift a little. Tell me about your introduction to dancehall. Was there a moment when it really hit you that this was your thing?

Walshy Fire: Honestly, there was never anything else. You know how some people date around before finding “the one?” This was like meeting that first love and never looking back. Dancehall was my first love. The first thing I ever really cared about deeply.

Jeff: Do you remember the first time you experienced a sound system?

Walshy Fire: Yeah, I grew up in Half Way Tree, Kingston. Sound systems were everywhere. Clubs—well, not “clubs” in the traditional sense. More like open lots with bamboo walls, maybe some concrete flooring. Skateland was right down the street.

Sound system culture in Jamaica is intense. It’s gotta be loud, well-presented, and just sound incredible. Even the buses had like ten speakers inside. It was like a moving concert. They’ve banned that now, but back then it was just part of life.

Jeff: Was it about who had the loudest or the most powerful sound?

Walshy Fire: Absolutely. Everything’s a clash in Jamaica. Bikes, sound systems, lyrics—it’s always a competition.

Jeff: That energy is unique to dancehall, right? That call and response?

Walshy Fire: Yeah. In dancehall, the person on the mic is as important as the music. Sometimes more important. The way they talk, how witty they are—it’s crucial. MCs push the culture forward with every new phrase or delivery. It’s constant sparring. Every night, someone’s throwing lyrical punches.

Jeff: You’re that guy today. You stand at the mic, controlling the energy in the room. Like a maestro, but wilder.

Walshy Fire: Way more radical. You have to go crazy. The more outrageous you are, the more the crowd loves you. Some of the younger DJs say the wildest things—it shocks me, but I also can’t wait to DJ with them.

Jeff: Sparring is like the electricity that makes dancehall work, and plug are dub plates. Can you explain what they are?

Walshy Fire: A dub is when you get an artist to record a custom version of a song—just for you. Sean Paul, for example, might shout your name in the track. It’s yours. No one else can play it unless you authorize it. Some of these dubs are from legends who’ve passed, like Gregory Isaacs or Dennis Brown. They’re priceless. Even with AI, you can’t replicate that authenticity.

Jeff: Let’s bring it back to the diaspora. Dancehall and reggae reached so far beyond Jamaica touching punk rock in the UK, dub in New York…

Walshy Fire: Yeah, it’s crazy. Jamaica is just a small island, but the cultural impact is massive. I don’t know a single person who doesn’t like reggae. Everyone recognizes Bob Marley’s face. We even argue—who’s more iconic: Michael Jackson or Bob Marley?

Jeff: That’s real. Marley had (has) a global message. It felt like he was fighting for something—and asking us to fight with him.

Walshy Fire: Exactly. Marley was a warrior. You felt like you were part of the struggle. Michael? He was legendary, but he didn’t have that same communal fight.

Jeff: That trust is important. If the audience doesn’t feel that, it changes everything.

Walshy Fire: Right. It’s like when an artist says something that changes your perception. I still love the music, but maybe I don’t feel as connected. Marley didn’t have that disconnect. He’s stayed pure in people’s minds.

Jeff: Let’s talk about your book “The Art of Dancehall.” Did you collaborate with other to track down key flyers?

Walshy Fire: Yeah, for sure. Especially with people like my guy Lee Majors from New York. Those Brooklyn flyers? Different level. The most gangster parties ever.

Jeff: I visited New York often in those pre-9/11 years. I remember the wildness. It was a time of freedom.

Walshy Fire: Totally. New York had a different presence. Remember when you could bring anything on a plane? It was a different world.

And that freedom is reflected in the flyers from that era.

Jeff: And you stopped the book at the year 2000?

Walshy Fire: Yeah. After that, everything changed. But also, that was the golden age of flyer design. Hand-drawn, DIY, cut-and-paste using magazine fonts—ransom note style. Kinko’s plug at 2 a.m.? That was the real hustle.

Jeff: Everyone had a Kinko’s guy!

Walshy Fire: Had to! Those guys made it possible. There was no other way to make flyers.

Jeff: Alright, one last question. Out of all the flyers, which one hits the heart?

Walshy Fire: Kilimanjaro vs. King Addies. The biggest sound clash in history. Kilimanjaro, top sound in Jamaica. King Addies, top sound in Brooklyn.

It happened around ’94 or ’95, and it was historic. Roadblocked. Game-changing. Or Rodigan vs. Barry G—that dub where Tenor Saw sings, “Straight from London to New York City…” still gives me goosebumps.

Jeff: That’s legendary. And didn’t Rodigan even clash with the ASAP Mob?

Walshy Fire: Yeah! And Rihanna did a dub for Rodigan dissing Rocky—who she’s now married to. Sound clashes bring people together in the most unexpected ways. Even rivals become friends afterward.

Jeff: Unless you can’t bounce back.

Walshy Fire: Right. If you don’t recover, the loss sticks. Like when Earth Ruler clashed with King Addies, and Babyface got called a “mendicant boy.” I didn’t even know what that meant, but the way the crowd reacted—you just knew he lost.

Jeff: That word echoed for months.

Walshy Fire: It stuck. That’s the power of sound clash culture.

Rebel Sound is a supergroup featuring David Rodigan, Chase & Status, Shy FX, and MC Rage, that was formed to compete against BBK, Stone Love and ASAP Mob during the 2014 Red Bull Sound Clash in London.